YA WARIS HAQ WARIS

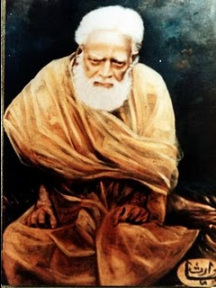

Syed Haji Waris Ali Shah

A Nineteenth Century Saint

Listen carefully! No doubt, there is no fear nor any grief upon the friends of Allah. (Quran, Sura Younas – Chapter 11)

Chapter I

In the first quarter of nineteenth century when the din and clash of empires had hardly subsided in Europe, when the Moghal empire in India was in its last throes and when the British rule was rapidly established in other parts of the country, a child was born in a quite town of Deva whose word and example were destined to influence the religious conceptions and ideals of an incredibly large number of human beings. He was Haji Waris Ali Shah of Deva. Deva is an ancient town north of Bara Banki, seven miles from the headquarters of District. Like other towns, it has not escaped the ravages of time. Unsightly ruins and mouldering walls meet the eye on every side, but the moral decay is no less remarkable than physical. Noted once as the birth-place of great Sufis and divines, it is now notorious as the hot-bed of intrigue and litigation.

Haji Saheb came from a family of Hussaini Syeds, distinguished for piety and learning. His genealogy shows that he was born in the 26th generation of Hazrat Imam Hussain. The name given to him had a particular significance. WARIS is one of the ninety-nine names of Allah (as used in the Quran) and indicates that after everything else has perished, He alone will survive. It was an ancient practice among the Sufis to seek annihilation in one of the Divine attributes which colored the whole of their existence and became its pre-dominant feature. The attribute in question involves the annihilation of self and the true recognition of the everlasting nature Deity. He cut him-self off completely from the world and attained the highest degree of self-abnegation. Thus realizing a particular aspect of his name which lives today though he is no more.

He was not even three years old when he lost both of his parents. He was regarded as something of an infant prodigy. At the age of five he started learning the Quran and learnt it by heart in a period of just two years. Though he seldom read his books, to the amazement of his tutor he always knew the answer when tested. He seemed to learn by intuition. He preferred solitude to books and often slipped away to out-of-the-way places. He spent long periods in retirement and contemplation. Once on a search being made he was a discovered in woods in a state of mediation.

His biographers are silent on the subject of his studies and the extent of his learning. It is certain, however, that he did not acquire much from books. Bu t in his advanced age people came from distant places to discuss theological questions with him. He had a dislike for controversy but his replies, though brief, generally silenced his adversaries and showed a thorough knowledge of the dispute. He could speak fluently in many languages; probably he picked up various languages in his extensive travels.

His brother in law, Haji Syed Khadim Ali Shah, who live Lucknow, was a man of great learning, and a Sufi of great stature. He took charge of the boy's education personally and when he was only eleven years of age, the elder Syed initiated him into the mysteries of occult science and gave him the necessary training. It was not long before Haji Khadim Ali Shah died and his mantle descended upon the boy. He was duly elected a successor of the deceased Haji Khadim Ali Shah.

At the age of fourteen he started initiating people in his order and had quite a number of disciples. The burning glow of divine love, however, impelled him in another direction. He was only fifteen when he started on a pilgrimage to Mecca. He gave away all his property including a valuable library, to his relations and destroyed the papers related to his landed estates. When he left home he possessed nothing in the world which he could call his own.

That his mode of living was ascetic even at this early age is shown by the fact that he ate only once in three days. For twelve long years he traveled in Arabia, Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia, Persia, Turkey, Russia and Germany. He performed Hajj ten times in the course of his travels. One of the most important rights of the Hajj is the temporary discarding of made-up clothes and the donning of Ahram (un-sewn piece of cloth wrapped around the body). The pilgrims resume their ordinary garb when the Hajj is over. From the date of his very first Hajj, he adopted the Ahram as his garb, and retained it throughout his life. He abandoned subsequently the head-dress and the shoes also. He visited the countries enumerated above without having ever ridden a horse or vehicle and only got into a boat when he had to cross the seas.

He visited Constantinople in the time of his majesty Sultan Abdul Majid 1. One day Haji Saheb was going around the palace gardens to which he was conducted by one of his disciples (a functionary at the royal palace) when the Sultan happened to arrive. He was so impressed the sight of the holy stranger that he offered himself to be admitted into his order and was duly initiated. Thousands of persons became his disciples during his sojourn in the countries which were once the birth place and strong hold of Islam. It is difficult to conceive that in his youth he should have obtained such proficiency in mystic knowledge as to inspire people much older than himself with deep faith in him and longing for a spiritual life, and that he should have been welcomed in the sacred places like the holy of the holies. Nor is there any instance on record of one so young starting life as a Darwaish and attracting so much notice, especially in foreign lands. With his inherent love of God he united great powers of the mind which are acquired by other mystics after long years of self-mortification and hard ecstatic discipline.

It is interesting to note that on the occasion of his visit to Berlin, Haji Saheb was a guest of Prince Bismarck. One cannot but miss an account of what past between the future statesman and the humble servant of God and how they came to meet each other.

He went on pilgrimage to Mecca seven times from India. Three times out of seven he performed the journey on foot, crossing the formidable hills of Afghanistan in naked feet. When he returned home after more than a decade, his own were initially unable to recognize him. His parental house was in ruins. He went round the village but no one came forward to welcome a Faqir. Some of his relations who heard of his arrival shunned him lest should claim his property which they held in their possession. He smiled at their coldness and remarked "they seem to think that I have come back for the sake of my property as if I care for it". He went away immediately and resumed his wandering life. He spent the major portion of his life in traveling. Though he paid frequent flying visits to the town of his birth but it was not till 1899 that he came to stay at Deva permanently at the request of some of his disciples.

Haji Saheb's asceticism led him to adopt a life of celibacy. It was quite in keeping with the conduct of one who renounced the world in early youth on account of soul consuming love of God. From this sacrifice of human affections it is not, however, to be imagined that he lacked tenderness of heart.

Being habitually absorbed in contemplations, he was a man of few words. He spoke quickly and in soft tones with down caste eyes. He often repeated his words to emphasize its meanings. He was particularly good and considerate to the poor, and his general bearing was one of humility. His exterior corresponded to his interior. His features were handsome, with an unusually broad and intellectual forehead. But his eyes formed the center of attraction. They possessed a magnetic power which was irresistible. When he walked in a crowd or assembly, he always seemed taller by the head. He never sat on a chair or sofa or used a bedstead. He slept in the floor throughout his life, but without a pillow. Some of his disciples state that he never actually fell into slumber.

If he once passed through a road or street he would go by the same way when he visited the place again. If carried by a different way he would turn back and follow the old route. He struck with the same tenacity to his resting places to his journey and to his hosts. It is one of those rare qualities of the mind from which spring lifelong friendship and affection. With him to know a man once was to know him always. He observed unusual silence during the first ten days of Moharram. He accompanied the Taazias sometimes and always stood up when a Taazia passed by his own house.

Reference has been made in the foregoing lines to his habit of fasting. From the age of fifteen to that of forty, he ate once in seven days. The interval was shortened subsequently to three. At the age of fifty, he had a severe illness and his medical advisors insisted on his having nourishments twice a day, even after his recovery. He followed their advice but his compliance was nominal. He proved by his example that man can live by God alone, though he cannot live by bread alone.

Chapter II

Before his esoteric teaching is dealt with, a word about Sufism will not be amiss. Unlike the "Eleusinian mysteries" of the Greeks (A society of cultivated Athenians in which the initiated alone could be admitted. They sought after a more adequate conception of the Deity than what was current in the popular religion) there is nothing mysterious about it. The legends and myths which form a halo round the lives of early Sufi saints have given a tinge if the supernatural to Sufism just as Freemasonry is associated by the common herd with magic. Founded on a desire for something deeper than mere formalism, Sufism stands on thoroughly orthodox ground. Ibn khaldun observes in his prolegomena that the fundamental principles of Sufism prevailed among the Companions of the Prophet and the followers, but in the second generation, when Islam grew more worldly, those who were religiously inclined lived a life of seclusion and piety. They had a coterie of their own and were nick-named "Sufis". The term Sufi was first applied to Abu Hashim Kura (800 A.D) though Hasan of Basra is regarded by some authorities as the leader of the movement.

Jami says in his life of Abu Hashim that the first convent for the Sufis was built by a Christian nobleman. This was the beginning of the monastic institution in Islam, which though opposed to the teaching of the Prophet, namely, that "there is no mockery in Islam" came to be adopted by the Sufis as part of their system. It was probably the desire for a life if retirement and seclusion which led ultimately in extreme cases to complete reunification of the world, otherwise the majority of the Sufis believed in being in the world but not of it. They were originally the object of much derision, and those who followed the letter of law looked askance at them as some Muslim sects still continue to do. But it was not long before they counted in their ranks famous theologians and learnt divines. Imam Shafai (a great canonist in Islam) has said that the knowledge of God possessed by the whole world did not equal his knowledge, yet it felt short of the knowledge possessed by the Sufis. In the third century of the Hijra, Sufi doctrines were considerably developed, and brought some of the more advanced members of the sect into conflict with the ecclesiastical authorities. It ended in the sentence of death being passed upon Mansoor Ibne Hallaj. The story is too well known to warrant a repetition. "whoso worships God by the light of ordinary religion is like one who seeks the sun by the light of the stars" is one of the beautiful sayings attributed to him. According to Bayazid of Bustam, one of the eminent Sufis of early period, "the performance of miracles is not the real test of a saint, but a goodly and righteous life". The yearning of the "inner light" seized the heart and imagination of the Islamic world, and Sufism grew to be the craze in religious circles.

The East has been noted for its mysticism. Before the advent of Islam mysticism was practiced not only by Hindus, but by Christians also, it was probably on this account that foreign writers were led to imagine that Sufism was derived from the theosophy if the Vedants or from Neo-Platonism. The great authority of Ibn Khaldun entirely repudiates the theory that Sufism was engrafted upon Islam. While differing in some respects from the ordinary Muslim view, it is based entirely upon the teachings of the Holy Quran and has nothing to exotic in it. The man who above all others gave to Sufism a permanent shape was Imam Ghazali who lived in the fifth century of Hijra. He was anxious to distinguish it from mere asceticism. He, therefore, brought Sufism into harmony with orthodoxy and placed it on a metaphysical basis. But Sufism is more of a practical science than a study if the things of the soul. To acquire an insight into Sufism, it is not sufficient to know the history if the sect. the very fi rst lesson in Sufism is beyond the reach of the average man, as it consists of self mortification combined with fervid piety. The secrets of the order were, therefore, originally imparted to the select few only who showed a desire and capacity for spiritual development. Hence there is a veil of mystery drawn over it.

The eternal order of the universe according to the Sufis is based on love. The word is used by them in technical sense. According to Maulana Rumi (604 – 672 A.H.) the greatest authority on Sufism, has, in famous "Masnavi", put forward theories which correspond exactly to those of gravitation and evolution. He has traced the origin of man from matter and described the various stages of evolution through which man has passed. That a Sufi saint should have discovered and discussed these theories, centuries before Newton and Darwin were born, is a matter worthy of notice of the Western scientists as well as of the younger generation of our students. One is inclined, in all fairness, to give the palm to the Eastern mystic for his superior knowledge of the laws of nature. All matter is composed if invisible particles or atoms which are drawn towards one another by mutual attraction. The same law exists in the organic world. He interprets this tendency of bodies to approach one another by mutual a ttraction. The same law exists in the organic world. He interprets this tendency of bodies to approach one another as LOVE. It is argued on the same lines that man, having been evolved out of matter as the highest form of creation and having been endowed with reason, must essentially claim still greater affinity with the divine and Absolute Reason. "Rightly to understand the love of God," says Ghazali, "is so difficult a matter that one sect of theologians has altogether denied the love of God as consisting merely in obedience……The love of Him springs from the knowledge of Him". But the chief cause of this love, it is explained, is the affinity between man and God which is referred to in the saying of the Prophet: "Verily God created man in His own likeness".

For the purpose of practical training in Sufism, it is necessary to go through certain ascetic exercises and observances under the guidance of a spiritual preceptor or Shaikh, as the Sufis call him. It is through him by means of concentration that one is linked with God when the mind has been chastened by long training. A great deal depends on the character of the Shaikh. The early Shaikhs were men of great piety and learning. With the decline in the true spirit of Islam as well as in learning, the tradintional sanctity of the order could not hold its own against the growing forces re-action.

In modern times the so-called Shaikh or Pirs introduced the system of offerings and cash presents (nazr) which, unlike their predecessors, they accepted freely to enable them to live in comfort and lead a life of leisured ease. This excited the jealousy of the pure theologians who earned a precarious living by indicting doubtful fatwas and leading the prayers in mosques. To their mutual detriment, the line that divided the two parties became more marked as time passed. The Sufis lost the learning of the theologians and the latter, the broad spirit, the ethical refinement and the toleration of the former. The disposition to worldliness changed the entire character of the coterie. Another fact among the series of causes which affected its high moral tone was the use of phraseology of human love for the love of God by the Persian poets. The analogy, when carried too far in less scrupulous surroundings, was calculated to result in bringing discredit to the cult as it subsequently did. The Shaik hs of old have now degenerated into professional Pirs-third rate men who claim to give passports to heaven and trade on the credulity of their followers at whose expense they are fed and pampered. They have also introduced other innovations, such as the worship of shrines and tombs, which are entirely opposite to the teachings of Islam. It may be noted here that much theological learning (which is on the wane now) is not necessary to obtain an insight into the practical side of Sufism. What is most important is the possession of the true love of God and zeal for spiritual advancement.

The form which spiritualism has taken in Europe and America is quite different from the spiritualism of the Eastern Sufis. In those countries it consists in table-turning, spirit-rapping and holding communications with the spirits of the dead through a medium. People in this country have long been familiar with séances, but it is wrong to associate such practices with Sufism. European spiritualists have begun to realize that séances are a hoax, founded on the tricks played by mediums. These dilettante experiments in the realm of the spirit are as far removed from the higher manifestations of the soul and its mysterious relations with the Creator as Metaphysics is from Logic. What distinguishes a high order of man or what constitutes human goodness, belongs to the domain of ordinary ethics; but when self-forgetfulness and self-sacrifice are carried to an extreme for the sake of attaining the highest beauty of the soul, one is said to have acquired the real knowledge of God. This is exactly w hat Sufism claims to teach. The pantheistic tendency, with which it became imbued subsequently under the influence of foreign ideas and particularly of Greek philosophy, was an unknown feature in ancient Sufism.

According to Spinoza, "to know God, as far as man can know Him, is power, self-government and peace." Haji Saheb was one of those men who knew God as He ought to be known. He was not the founder of any sect or creed, but he was a man of uncommon power and goodness. The keynote of his system was "divine and universal love". The English poet appears to have been inspired by the same sentiment when he said:

Love rules the Court, the camp, the grove;

For Love is Heaven and Heaven is Love.

It was love which fired the soul of the great Rumi and made him burst into the following strain:

Hail to thee then, O Love, sweet madness!

Thou who healest all our infirmities!

Thou art the cure if our pride and our self-conceit

Thou art our Plato and our Galen!

It is interesting to find an echo of the old Sufistic theory in the writings of the Western spiritualists of today. A well known American writer (Ralph Waldo Trine – "In Tune with the Infinite") on spiritualism says:

"The moment we recognize ourselves as one with the spirit of Infinite Love, we become so filled with love, that we see only the good in all, and when we realize that we are all one with this Infinite Spirit, we realize that we are all one with each other…..that the same life is the life in each individual. The prejudices go and hatreds cease. Love grows and reigns supreme".

Haji Saheb asked his disciples to love him and to love one another, and laid great stress on this point.

A Sufi has to pass through several stages in the up-hill path of knowledge, which he seeks. Haji Saheb does not, like other Sufis, appear to have advanced by stages in the pilgrim's progress. He is said to have been as proficient in spiritual knowledge in his youth as he was towards the close of his life. He is, on this ground, believed to have been born a saint. It is averred further that he derived inspiration direct from the Caliph Ali (R.A) who is believed by Sufis to have received his spiritual training from the Prophet himself.

In the early stages of training a beginner is required to learn two most improtatn practical lessons, namely, complete dependence upon God (Tawakul) and resignation to the Divine Will (Taslim o Raza). The word Tawakul in ordinary parlance signifies trust in God, but has been much abused by a certain class of Muslims who are religiously inclined. Thousands of men who can do useful work live upon alms and charity in convents and schools and believe that they are following the teachings of their religion, inasmuch as they depend upon God alone for their means of subsistence. This has killed the spirit of self-reliance and increased the number of unproductive units in the community. The Sufis use the word in quite a different sense as explained by Ghazali:

"When the veil of secrecy is removed, one finds by actual observation that nothing other than God is self-existent; that causality is mere delusion and that He is the real cause and agent of all that takes place in the world. In this ecstatic state the Sufi becomes independent of all external agency and relies upon God alone for his wants".

It has been said that Haji Saheb gave away all his property when he left home. The house in which he came to stay in later years was not his own. Some of his disciples made arrangements for his food and brought it to him, but he never asked for it. He did not accept nazr, and never touched money with his hand. People sometimes made presents to him. He did not reject them, but gave them away to other persons. The true test of a faqir, he said, was that he should not ask for anything, not even of God. The love of God is the extinction of all other loves and desires.

As for the resignation to the Divine Will, he showed a stoical indifference to the disagreeables of life. He is not known to have ever complained of even of the weather. When he happened to be unwell, it was a hard task for the medical attendant to elicit from him what his trouble was. He never said a word that might convey the sense of suffering and contended himself with saying that nothing was wrong with him. He did not like to hear other people speak of their troubles, and enjoined complete acquiescence in the will of God. Far from claiming to interfere in the decrees of Heaven (as some faqirs pretend to do) he moved in perfect harmony with the Divine Will, thus expressing man's responsibility of becoming a co-worker with nature in the divine scheme of things. This is the highest form of self-control and submission to the Eternal Law.

The final stage in spiritual progress Fana or the state if being merged in God. But there is still higher state termed Baqa which is the continuance of annihilation in the Eternal Consciousness. It is the crown of spiritual attainment and the acme of self-annihilation. Some philosophers hold that to look with admiration on a type of perfect excellence is the way to become assimilated to that excellence. The Sufis believe similarly that constant contemplation and dwelling on the attributes of the Supreme Being result in union with Him.

Chapter III

Haji Saheb was possessed with the Divine Idea that he had practically lost all self consciousness. It is remarkable that he never mentioned his own name. Nor did he ever write it with his own hand. It may be taken as an indication of the fact that he ahd so effaced himself as to be unconscious of his own existence as a separate entity. "in that state" (that is, Fana) to use the words of Imam Ghazali, "man is effaced from self so that he is neither conscious of his body nor of outward things. Even the thought that he is effaced from self should not occur to him. The highest state is to be effaced from effacement". This was doubtless the state which Haji Saheb had reached. "The man that knows God best", said Zunnun Misri, "is the one most lost in Him".

The inward bent of Haji Saheb's mind prevented him from holding him long discourses, and this accounts for the lack of any systematic teaching for which we search in vain in the record of his long life. He was one of those saints whose thoughts are altogether absorbed in the contemplation of the Majesty of God and have no room for anything else. His biographers have, however, collected some of his percepts, a few of which are:

- Divine love cannot be acquired. It is a gift of God.

- There is no method in love.

- Distance does not count in love. If you love me, I am with you even if you are at a distance of thousands of miles.

- Love is akin to faith

- The universe is governed according to the sentiments of the lovers of God.

- Do not carry your want before God even if you are starving, for He knows everything.

- Real worldliness is forgetfulness of God.

- A true faqir is never in want.

- Islam is not identical with faith.

- Remain always the same.

- What you do once, continue to do it.

- Trust in God. If you rely upon Him truly, you need not worry about your daily wants.

- Faith should be free from doubt.

- Not a breath should pass without remembrance of God.

- It is no use going to the Kaaba for those who cannot see God here.

- The same God is to be found in the mosque, the church and the pagoda.

- God does not live on the empyrean. He exists everywhere. One who cannot see God in this world is blind.

The last two may not inaptly be compared with the concluding words of St. John's First Epistle:

"Beloved are the sons of God…. we know that when He shall appear ….. we shall see Him he is".

These maxims only point to the transcendental doctrine common to the majority of the Sufis that God alone has real existence. Everything else is non ens. This is a great controversial point between the Sufis and the theologians, there being disagreement among the Sufis themselves. A section of them is opposed to the pantheistic view that "all is God" and believes in its reverse the "God is all" and accounts for the universe as a manifestation of His various attributes, though acknowledging that the whole creation is bound in one definite and consistent unity. There seems, however, nothing heterodox in the Sufistic view which is supported by the following verse in the Holy Quran. The Almighty said, addressing the angels, "When I have made him (i.e. man) complete and breathed into him of My Spirit, kneel before him". (Part XIV, Chapter XV). There are more than one verse to this effect in the Holy Book. For those who believe in it, no further proof is needed of the fact that this "quintessenc e of dust" has within him the Divine Spirit. How strange that the pagan philosopher, Epictetus, should have exclaimed hundreds of years before the Book of God was revealed: "Thou art a piece of God, thou last in thee something that is a portion of Him. Unhappy Man! Thou bearest about with thee a God and knowest it not!".

It is the realization and development of the divine element of one's nature which the Sufis aim at. Sufism is essentially a cosmopolitan creed, but Haji Saheb enlarged its bounds to the extent which it had not known before. He admitted freely into his order men and women of every religion, caste and creed. He declared openly that Muslims and Hindus, Magians and Christians were all one in his eyes. In his presence one felt truly the touch of nature which makes the whole world kin.

There are three important schools or monastic orders of Sufis, namely Qadriya, Chishtia and Naqshbandia. Haji Saheb belonged to the first two. Unlike other Sufis darweshes he did not initiate people privately. He had different formulas for members of different faiths. When initiating with Jews and the Christians he used the following words:

"Mosses, Christ and Mohammad are all three apostles of God. If you do not believe in any one of them, do not speak ill of him. Abstain from unlawful things".

According to the Holy Quran, God made no distinction among the Apostles. His teaching was, therefore, based entirely in the word of God. It will not be out of place to refer here ti another verse in the Book which says that "the nearest in friendship to Muslims are those who call themselves Christians, for they have among them (learned) priests and monks who behave with humility". (Part VI, Chapter V). Every Christian ought to read these lines. In view of the past conflict between Christianity and Islam, it is high time that Europe rose to the realities of the moment and revised its knowledge of Islam by proper study and by casting off old prejudices and wrong notions disseminated by ill-informed European writers especially Missionaries. Will a union between Islam and Christianity be a great political asset, is a question for European statesman to consider.

To the Hindus he said:

"Believe in Brahma. Do not worship idols. Be honest". With him there were no distinctions if meum et tuum. Thousands of Hindus, including Sadhus and faqirs of different panths, paid homage to him and entered his order. He always welcomed them in these words:

"You and I are the same". He recognized God in every individual, because he had first realized Him in himself.

He did not ask non-Muslims to abjure their religion. On the contrary he advised them to follow it with greater zeal and sincerity. For those who belonged to any profession or trade, he often added a few words of advice which had a bearing on their individual calling. If any person showed an eagerness, after the pledge had been taken, for a religious life and chose to retire from the world, he was given a tahband (a garment similar to his own which has come to be recognized as the badge of the order) and received some verbal instructions, with the direction to leave for some far-away place where he was to stay and go through the prescribed course of training. The ascetic discipline which the novices were required to undergo was the hardest ever known. For example, one was asked to keep his eyes open which meant that the man was to deny himself solace of sleep for the rest of his life. Another man was directed to give up all kinds of food and to live on such fruit as he could pick up in the j ungles. After a certain period he was only to smell the fruit when there was a craving for food, and at the final stage he was to content himself with simply looking at it. The teaching was not the same for everyone. It varied according to the capacity of the individual. As a rule for those who invested with the garb of the order were given a nick-name. It will not be out of place to refer in this connection to a ceremony originated by Haji Saheb's disciples. When a new ahram was brought by ay any one of them, he was requested to change, and the one he had on was taken away by them. It was held in such deep veneration that it was impossible for any one to get the whole ahram. It was torn into pieces which were distributed as relics. The avidity of his disciples to possess themselves of these relics was carried so far that on same occasions he had to change several times in the course of day. The ahram was sometimes brought before him to the accompaniment of music.

His disciples may broadly be divided into two classes-the Khirqa Posh (those who embraced the ascetic life) and the "Men if the World" (those who adopted his doctrine but made no ostensible change in their ways of life). The Khirqa Posh may again be subdivided into those who were considered to be fully qualified and received the ahram and those who assumed the garb of the order without permission and were quite innocent of spiritual training.

The "Men of the World" outnumbered the Khirqa Posh. His biographers confess their inability to estimate the number of his disciples, as they are scattered all over the Asiatic continent and parts of Europe. Haji Saheb did not invite or persuade any one to enter his order. He was adored wherever he went. The extraordinary spell exercised by him not only on the popular mind, but on the rich and poor, the educated and the uneducated alike, can only be accounted for by the principle that if you would have all the world love you, you must first love all the world. The railway stations and streets of the towns which he visited were thronged with crowds. It is said that on the occasion of his first visit to Darbhanga there was such a rush in the house where he was staying that one of the doorways collapsed and he was moved to another part of the building. The initiation occupied the whole day and yet the crowd did not seem to thin. When he left the place about 10,000 people followed him. He stopped in the way and desired that his palanquin be placed on a raised piece of ground so that the people may touch it in token of their being included among his followers. On another occasion the crowd was so dense at a railway station that no one could pass through, though everyone wanted to be near him to be initiated. He looked around and said "You all are my disciples, go". A departure was made from the ordinary method of initiation when the crowd grew too thick to permit every person being formally initiated, and a rope or a sheet was held out, the far of which people were required to touch.

Of his European disciples who had received some training, three were known as Walayti Shah. A strange story is told about of a Spanish nobleman of the name of Count Galarza who came all the way from Spain to pay a visit to Haji Saheb and to be initiated in his order in London. A disciple of Haji Saheb who was interested in spiritualism made an exhibition of his powers. They were often thrown together, and the Count hearing if the greatness of his saint set his heart on seeing him. An interview was arranged through a Muslim student (another disciple of Haji Saheb) who was returning to India after being called to the bar, and the Count arrived in Deva eventually. In the course of the interview Haji Saheb said to him:

"You have come and are united with me. Blessed be your coming. You and I shall be there together".

The Count appears to have been well satisfied with the result of the interview, for on his way back he wrote from Paris to a member of his order in Deva to the effect that he perceived how the Saint had been with him in the Divine path from the first to the last.

There has not been a prophet or saint since the beginning of the world who has not had his opponents and whose conduct has not been the subject of adverse criticism. Despite his saintly life and Catholicism, Haji Saheb was not regarded as model of orthodoxy by a certain class of Muslims who were inclined to be pharisaical. The main charges against him were that he did not say his prayers regularly (i.e. five times a day) and that he admitted all sorts of people into his order who, owing to the want of proper teaching, displayed great laxity in the performance of religious duties. The first charge arose partly from "odium theological" and partly from misapprehension. It is true that Haji Saheb did not say his prayers like ordinary Muslims but he did so at times. There is absolutely no evidence of the fact that he ever departed from the recognized tenets of the faith. He held fast by the book of God, and if he did not outwardly observe the letter of the law, it was because he remained always in mantic state. According to the Sufi doctrine, a Sufi darwesh while in the state of sukr (intoxication) is exempt for the time being from the religious obligations, imposed on those who are in a state of "sobriety". The term "intoxication" is applied to a God-intoxicated man and is used to denote the rapture of love for God – a state in which all human attributes are annihilated and one sees nothing but God. "When the gnostic's spiritual eye is opened, his bodily eye is shut". Haji Saheb has himself put it that he could not with propriety address Him, as if He was absent, and go through the pretence of saying his prayers. He disliked all formalism and seemd to agree with great Rumi who says:

"Fools exalt the mosque, but ignore the true temple in the heart".

A reply given by him to a theologian on the same point was typical of him:

"If anyone sees God and kneels before Him, he is called a heretic, but those who kneel without seeing are described as true believers".

As regards the second charge, it must be conceded that his readiness to take men of all creeds into his order strikes one at first sight as an innovation or a departure from the established practice; but it is only a proof of the higher powers of his mind. Besides being a sign of great sage, it goes to show how far he excelled other Sufi darweshes in breadth of vision and was the first to open the gateway to Sufism so wide as to admit into it people of different faiths. He stands unique in this respect among the members of his fraternity. Like Christ who ate with plebeians and sinners, Haji Saheb took the good and the bad alike into his fold.

Those who are true to the Highest within them can call forth the good in each individual who is brought into contact with them. He taught by example and not by precept – by living the life and not by dogmatic teachings as to how it should be lived. In life, as in art, the only profitable method of teaching is by example. Our Prophet exemplified in his person what he preached and the same is true of his predecessors, Moses and Christ. He impressed on his disciples the fact that one should pray to God for the sake of praying and not with a view to any future reward. It is difficult to conceive of a higher standard of religious teaching. It may be said that the ideal placed before his disciples was too high to be attained by the average man. It is impossible, however, to comprehend the vast moral amelioration effected by his teaching.

Haji Saheb never claimed any extraordinary powers for himself, but there are innumerable instances on record of his healing the sick with a glance or by a touch things done in the ordinary routine of life seemed to order on the supernatural. Once on his way to Bahraich he wanted to cross the Gogra, but no boat was available at the ferry. He decided to swim across the river with his companions who were in a state of terrible fright and reluctant to follow him; but they were astonished to find the water only knee-deep when they got in and simply waded through. What was a matter of everyday experience for those who lived in his company may sound incredible now, namely, that his feet never showed any sign of dirt though he always remained barefooted, nor did they leave any mark or impression on the carpet when he walked into a room. Most people did not believe it. Some of them invited Haji Saheb to their houses to try the experiment. They had the floor spread with white linen and had the groun d in front of the house well watered. To their great surprise they failed to discover any mud stain on the linen which, to be sure, was carefully examined as soon as he was gone.

When a man identifies himself with God the powers of God are manifested through him unconsciously. In the degree the human will is transmitted into the divine will and acts in conjunction with it does it become supreme. According as the effects produced by the powerful soul are good or bad they are termed miracles or sorceries. These souls differ from those of the ordinary people in three ways:

- What others only see in dreams they see in their walking moments

- While the wills of other people affect their own bodies a saint by will – power can move extraneous to himself.

Haji Saheb's life reminds one in an obscure way of the life of Christ. Some authorities on Sufism hold that a Saint sometimes takes one of the apostles for his model and concentrates his attention on certain aspects of life till he has absorbed in his own person some of the excellences of that particular apostle. They thus speak of willayat-i-Ibrahimi, willayat-i-Eeswi, willayat-i-Mohammadi, etc. There is nothing incongruous in the idea that Haji Saheb should have followed the example of Christ who had marked spiritually, inasmuch as the Prophet of Islam combined in his person all the powers and goodness of Mosses and Christ in addition to his own. If a Muslim saint has something of the Christ in him, it may safely be inferred that apart from being a true follower of Islam he possess in an eminent degree of qualities attributed to Christ. After all the "sons of desert" and their descendants bear a greater affinity to Christ than his followers in Europe. One of the peculiarities of such a saint is that he can influence his disciples as well as other people spiritually by a touch of his hand or his garment. This seems to account for peculiar method of initiation introduced by Haji Saheb, namely, the fact of a novice being required to touch the hem of a garment or the end of a cord passed round to him. He often expressed his satisfaction by patting one on the back or giving mock blows.

The Hindus regarded him as an incarnation of Sri Krishna while some of his great contemporaries looked upon him as a perfect image of his prototype, the ancient Sufis. All of them acknowledge his superiority. It will be sufficient to give the following extract from the opinion of one of his contemporaries, namely Maulana Shah Mohammad Akmal Afandi of Baghdad:

"Haji Saheb has no equal in this age. The degree of gnosis attained by him is unsurpassed. I have seen a number of Darweshes and Shaikhs and have traveled much, but I have not come across on who could approach him".

Chapter IV

The question now arises: What was the purpose of his life and were the times in which he lived and moved particularly favorable for the birth of a saint?

The history of India after the first half of the nineteenth century is closely connected with the history of England. The government of the country having been taken up by the Crown, it was natural that the scientific and intellectual activities of the great Victorian age should have their influence over this country. It was the dawn of English education among us. The impact of Western ideas after long years of mental lethargy in the East brought about a rude awakening. So far as the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh were concerned the appearance on the scene later of the reputable champion of the Western civilization and culture – Sir Syed Ahmed Khan – revolutionalized the whole Muslim community. In his anxiety to model the rising generation on Western lines he applied the pruning knife to religion first. An attempt was made to reject the ancient theories and traditions and to explain away the rest in terms of European science and philosophy. The new movement, termed by the orthodox as the "naturalistic" movement, threatened to shake the foundations of the faith. But nature always adjusts its forces. In the midst of this welter of ideas when materialistic tendencies were growing on one side, a dazzling spectacle of spiritualism was presented on the other. Haji Saheb was not a hierophant or a preacher. He did not oppose the spread of English education. An interesting story is told of an interview between Haji Saheb and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. Haji Saheb happened to visit Aligarh. Sir Syed on hearing of his visit, sent a message to him requesting for a private interview, and he was asked to come in the evening. Sir Syed arrived late in the evening after dinner and knocked at the door. One of the servants inquired as to who was there. The visitor answered that it was the Satan. Haji Saheb got the door opened at once and received him most cordially. The interview lasted longer than usual. Sir Syed complained about that the members of his own community called him a heretic or even an infidel. Haji Saheb rejoined that a Syed could never be a disbeliever in God and added: "I am not at all opposed to English education, but faith, love and sincerity are great essentials". Haji Saheb was as popular with the anglicized youth as with the people of the older generation. English-knowing men flocked to him by hundreds and sat at his feet. He is the first Sufi darwesh who crossed the seas and visited Europe as he is also the first to have attracted the English-knowing class. His existence which covered the greater part of the century was a practical protest against the supremacy of matter over mind and he represented a type of godliness and righteousness before which the disturbing forces of unbelief gave away.

The work of initiation was carried on till the last moment of his life, and he passed away on the 7th of April 1905 after a brief illness. One stands in awe and pictures to oneself the four score years of self-imposed suffering, the seven days fast, the barefooted journeys, the endless wanderings, the wakeful nights, the ceaseless breathing of the name of God, the heart filled with love and head bowed to the Maker in absolute resignation! He was a monarch in the domain of Sufism. His great humanity and his wide sympathies enabled him to break from the artificial bonds of religion and to make the people of different castes and creeds shake hands with the followers of his sacred order. He achieved by the silent force of example what was never accomplished by the tongue or the sword. His mission was to teach the love of God as well as universal love. He did so by practicing what he preached, rallying men of conflicting creeds under a common banner, conquering all earthly desires and by merging t he finite in the infinite, thus fulfilling God in man.

He was buried on the spot where he died. It is now marked by a splendid monument – one of the finest in Oudh – erected in his memory by some of his devoted followers. The flight of steps leading to the tomb are worn daily by the footsteps of a stream of pilgrims, but the gathering is the largest on the occasion of his death anniversary when a religious fair is held at Deva. The cult continues to progress, for every year at the time of the Urs.

On Haji Saheb's death a dispute arose about succession which resulted in a law suit and the creation of a trust. It is recorded on good authority that he made a formal declaration to the effect that no one was to be appointed his successor. He used the following words: "Love is better than formal righteousness. My creed is love and a lover has no successor". It is not necessary that every Sufi darwesh or Shaikh must have a successor. The principle underlying the appointment of a Sajjada Nashin originally was that he should continue the spiritual line by carrying on the esoteric teaching of his predecessor in addition to imparting theological instruction; for in the early days of Sufism a monastery or a mosque was partly used as a seminary also. It was an indispensable qualification for a Sajjada Nashin that he should at least be a man of outward piety, besides learning. If a Shaikh failed to nominate a successor none was appointed. Sometimes one of the disciples best qualified for the purpos e was elected by the majority of the members of the sect. The office has been degraded these days owing its conversion into a source of gain, and it has lost its pristine sanctity.

I cannot end without making in humble reverence the confession that I have not been able to do justice to the subject, for the simple reason that Haji Saheb belonged to that great company who are the true servants of God, but who are far removed from our understanding as they are near to Him.

Acknowledgement:

This paper was originally written and published in 1922 by Syed Iftikhar Hussain Warsi Kakorvi on the personal request of Sir Richard Burn. Keeping in view the modern English in practice now a days, we have made a few minor changes in it.

Genealogical Table

Waris Ali Shah is a Direct Descendent of Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him). The Genealogical table of Waris Ali Shah also testifies that the Direct Lineage of the Hussainy Syeds (ie without any side lines like cousin/uncle etc) finished at Sarkar Waris since he was an eternal bachelor and never married.

Below is his genealogical table:

Prophet Muhammad (Peace and Blessings be Upon Him)

Bibi Fatima (d/o Prophet Muhammad PBUH, married to Ali-Murtuza)

Imam Hussain

Imam Zain-ul-Abidin

Imam Muhammad Baqir

Imam Jaffer Sadiq

Imam Musa Kazim

Syed Qasim Hamza

Syed Ali Raza

Syed Muhammad Mehdi

Syed Muhammad Jaffer

Syed Abu Muhammad

Syed Askari

Syed Abul Qasim

Syed Mahrooq

Syed Ashraf Abi Talib

Syed Aziz-ud-din

Syed Ala-ud-din

Syed Abdul Alad

Syed Abdul Wahid

Syed Umar Shah

Syed Zainul Abidin

Syed Umar Noor

Syed Abdul Ahad

Miran Syed Ahmad

Syed Karamallah

Syed Slamath Ali

Syed Qurban Ali

Syed Waris Ali Shah